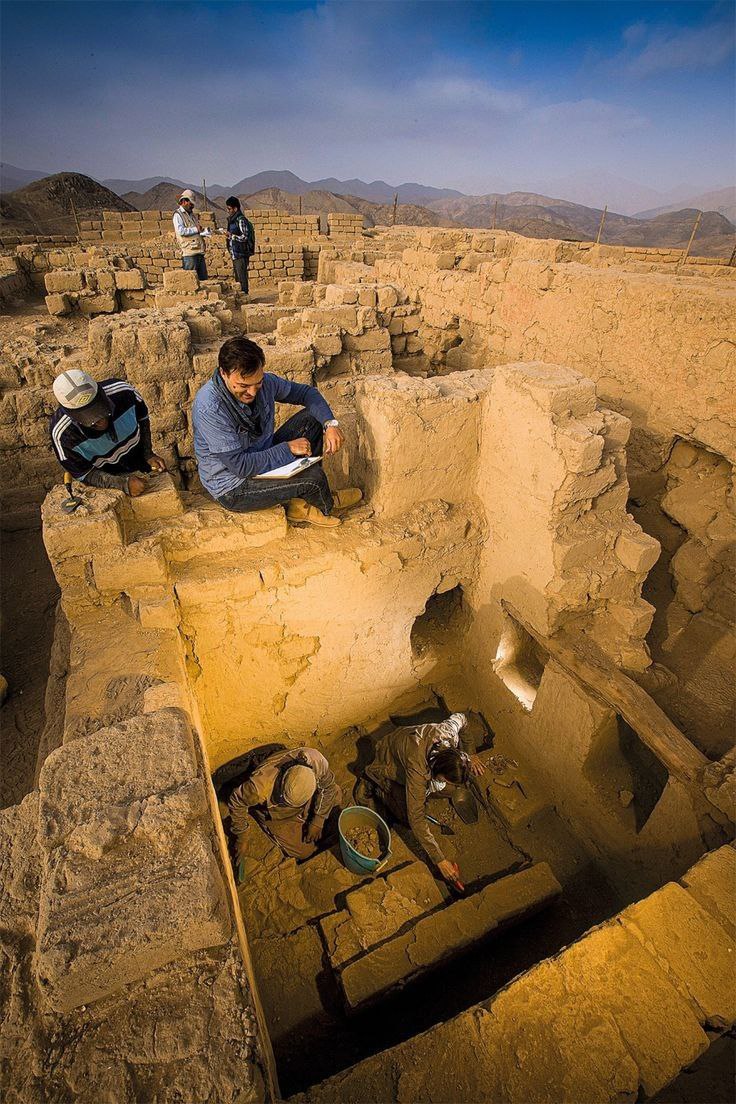

More than a thousand years ago in what is now Peru, the site of El Castillo de Huarmey was among the land’s most sacred places; University of Warsaw archaeologist Miłosz Giersz was sure of it. Plenty of people had warned Giersz that excavating there would be difficult and almost certainly a waste of time and money. Looters had already been tunneling into the massive hill, searching for ancient tombs and treasure. Located on the coast, a four-hour drive north of Lima, what was once a holy place was pitted with holes, looking more like a moonscape littered with ancient human bones, and strewn with modern trash.Looking past the debris, Giersz was entranced by the bits of textiles and broken pottery he saw dotting the slopes. They came from Peru’s little-known Wari civilization, whose heartland lay far to the south. In 2010 Giersz and a small research team began investigating by imaging what lay underground with a magnetometer and taking aerial photos from a camera sailing above on a kite. The results revealed something that generations of grave robbers had missed: the faint outlines of buried walls running along a rocky southern spur.

(Did hallucinogenic booze fuel politics in ancient Peru?)

Working with Peruvian archaeologist Roberto Pimentel Nita, Giersz and his team dug there, and the faint outline turned out to be a massive maze of towers and high walls spread over the entire southern end of the site. Once painted crimson, the sprawling complex seemed to be a Wari temple dedicated to ancestor worship.In fall 2012, as the team dug down beneath a layer of heavy trapezoidal bricks, they discovered something few Andean archaeologists ever expected to find: an unlooted royal tomb. Inside were interred four elite Wari women—perhaps queens or princesses—accompanied by as many as 54 other highborn individuals, six human sacrifices, and more than a thousand grave goods, all of the finest workmanship—from huge golden ear ornaments, silver bowls, and copper-alloy axes to exquisitely crafted textiles and colorful ceramics.The Wari

Around the seventh century A.D., the Wari emerged from obscurity in Peru’s Ayacucho Valley, rising to glory long before the Inca, in a time of repeated drought and environmental crisis. They became master engineers, constructing aqueducts and canal systems to irrigate their terraced fields.Near the modern city of Ayacucho, they founded a sprawling capital, known today as Huari. At its zenith, Huari boasted a population of as many as 40,000 people—twice the population of Paris at the time. From this stronghold the Wari lords were able to extend their domain hundreds of miles along the Andes and into the coastal deserts, forging what many archaeologists call the first empire in Andean South America, which would grow to cover nearly the entire Peruvian Andes and coast.

(Get a taste of Peru’s hot potatoes, a staple crop in the country.)

Researchers have long puzzled over how the Wari built and governed this vast, unruly realm, whether through conquest or persuasion or some combination of both. Unlike most imperial powers, the Wari had no system of writing and left no recorded narrative history, but the rich finds at El Castillo, a journey of some 500 miles from the Wari capital, began filling in many blanks.

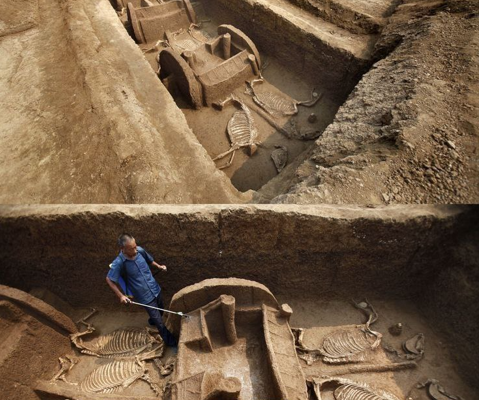

After the Wari had established firm control of the region, the new lord constructed a palace at the foot of El Castillo, and over time he and his successors began transforming the steep hill above into a towering temple devoted to ancestor worship. To rub shoulders in death with members of the royal dynasty, nobles staked out places on the summit for mausoleums of their own. When they had exhausted the available space there, they engineered more, building stepped terraces all the way down the slopes of El Castillo and filling them with funerary towers and graves.So important was El Castillo to the Wari nobles, Giersz explained, that they “used every possible local worker.” Dried mortar in many of the newly excavated walls bears human handprints, some left by children as young as 11 years old. When the construction ended, likely sometime between A.D. 900 and 1000, an immense crimson necropolis loomed over the valley. Though inhabited by the dead, El Castillo conveyed a powerful political message to the living: The Wari invaders were now the rightful rulers.“If you want to take possession of the land,” archaeologist Krzysztof Makowski said, “you have to show that your ancestors are inscribed on the landscape. That’s part of Andean logic.”The tomb

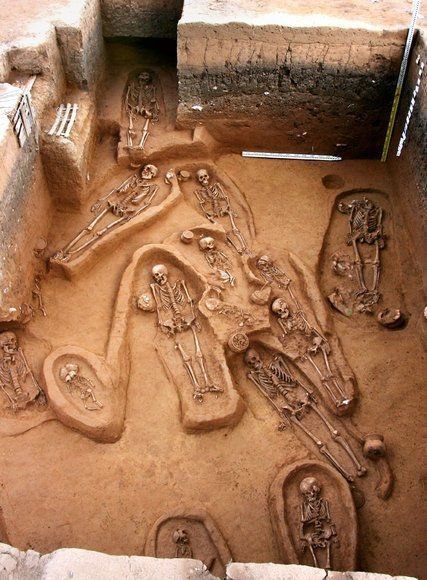

The intact chamber uncovered in 2013 lay along the western slopes of the necropolis. Wari builders had carved out a subterranean chamber that became an imperial tomb. Almost all of the deceased buried inside the chamber were women and girls who had likely died over a period of months, most probably of natural causes. Four of them appeared to be of higher rank than the rest.The Wari treated these four noblewomen in death with great respect. Attendants dressed them in richly woven tunics and shawls, painted their faces with a sacred red pigment, and adorned them with precious jewelry, from gold ear flares to delicate crystal-beaded necklaces. Their bodies were arranged in the flexed position favored by the Wari and then wrapped in a large cloth to form a funerary bundle.

Rich offerings were placed in small chambers, including textiles valued more highly than gold; knotted cords known as khipus (quipus), used for keeping track of imperial goods; and the body parts of the Andean condor, a bird closely associated with the aristocracy. (Indeed, one title of the Wari emperor may well have been Mallku, an Andean word meaning “condor.”)Social rank appears to have mattered as much in death as it did in life. Attendants placed the highest ranked women in three private side chambers in the tomb. The most important of all, a woman of about 60, lay surrounded by rare luxuries, from multiple pairs of ear ornaments to a bronze ceremonial ax and a silver goblet. Perhaps most valuable were weaving tools fashioned from gold. Wari women were consummate weavers, producing tapestry-like cloth with yarn counts higher than those of the famous Flemish and Dutch weavers of the 16th century.Nicknamed the Huarmey Queen, her remains revealed more details about an elite woman’s life in Wari culture. Careful examination of her skeleton revealed that she spent most of her time sitting, though she used her upper body extensively—the skeletal calling cards of a life spent weaving. In addition, she was missing some of her teeth—consistent with the decay that comes with regularly drinking chicha, a sugary, corn-based alcoholic beverage that only the elite were allowed to drink.Oscar Nilsson is well-known among archaeologists for his lifelike facial reconstructions of peoples from the distant past. Five years after the discovery of the intact tomb at El Castillo de Huarmey, Miłosz Giersz‘s team wanted to reconstruct the face of its most important occupant, the woman known now as the Huarmey Queen. They knew exactly whom to turn to.

Nilsson’s approach to the work is very “hands on” rather than relying solely on computer scans. To re-create the queen’s face, he first scanned the skull to create a 3D printed model as the base. Scientists had assessed the woman’s age (estimated to be about 60 years old), ethnicity, and weight, which allowed Nilsson to estimate the approximate thickness of her flesh. Plasticine was used to sculpt her features and then silicone “skin” was placed over them.

The queen’s hair had been well preserved, allowing Nilsson to mimic her style with a wig of human hair (from an elderly Andean woman and purchased in a Peruvian wig shop). From start to finish, the entire process took Nilsson 220 hours to create the astonishing work, giving people the chance to gaze upon this woman’s royal visage once more.Beyond, in a large common area, the lesser noblewomen were interred along the walls. Beside each one, with few exceptions, there was a container roughly the size and shape of a shoe box. Made of cut canes, it held weaving tools, the kind favored by the Wari to create textiles.

All of the noblewomen buried at El Castillo were clearly dedicated to this art. When the tomb was ready for sealing, laborers poured in more than 30 tons of gravel and capped the chamber with a layer of heavy adobe bricks. This tomb would remain undisturbed for centuries, keeping Wari wealth, knowledge, and tradition intact.

(The high-altitude quest to save alpacas in Peru.)

Today, researchers remain uncertain about why the Wari empire collapsed. One of the leading theories is that a severe drought struck their region around a.d. 1000. When the end came, it was swift. At one Wari site dedicated to making ceramics, potters seem to have dropped their tools one day and left, perhaps driven out by some as yet unidentified invader. The Wari left a history-changing legacy, though. They had created something in the Andes that never completely vanished: the idea of an empire. Four hundred years later, building on their foundations, the Inca emerged to revive it.